The dance between urban infrastructure and vehicle maneuverability has always been a delicate one. Among the many factors that engineers and city planners must consider, minimum turning radius stands out as a critical yet often overlooked element. This unassuming measurement dictates how effortlessly a vehicle can navigate tight corners, alleyways, and complex intersections—making it the unsung hero of urban mobility.

At its core, minimum turning radius represents the smallest circular turn a vehicle can make without skidding. While this might seem like a straightforward mechanical specification, its implications ripple through every layer of urban design. From the width of residential streets to the layout of parking garages, this single measurement influences decisions made by automotive engineers, architects, and municipal planners alike.

The human factor in turning geometry becomes apparent when we observe drivers navigating cramped European city centers or dense Asian markets. Vehicles with tight turning radii move through these spaces like fish through water, while those requiring wider arcs create bottlenecks and frustration. This difference explains why certain car models become beloved urban companions while others remain confined to suburban driveways.

Public transportation presents particularly fascinating case studies in turning radius optimization. The iconic London Routemaster bus, with its legendary maneuverability, could negotiate turns that would leave modern articulated buses stranded. Contemporary transit designers now face the challenge of accommodating longer vehicles while maintaining acceptable turning capabilities—a balancing act that often results in innovative steering systems and wheel configurations.

Emergency vehicles add another layer of complexity to this equation. Fire trucks and ambulances must maintain relatively large turning radii due to their extended wheelbases, forcing cities to design wider intersections and modified curb geometries in critical areas. These adaptations often create visual inconsistencies in streetscapes, revealing the hidden priorities of urban safety planning.

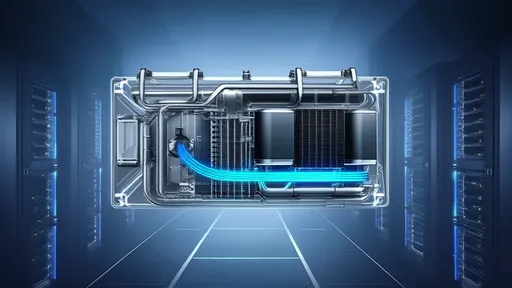

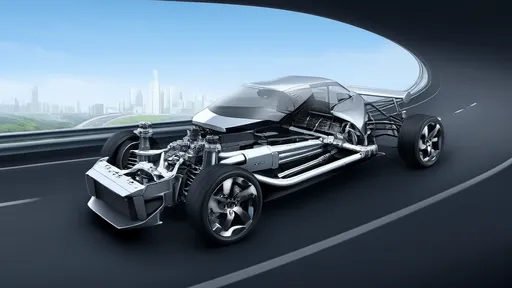

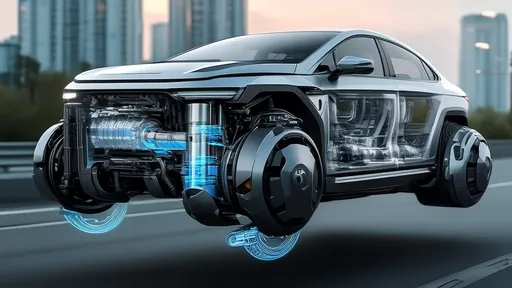

The rise of electric vehicles has introduced new variables into the turning radius equation. Without bulky internal combustion components, EV designers can reimagine vehicle architecture from the ground up. Some manufacturers have exploited this freedom to create revolutionary steering systems that allow wheels to turn at extreme angles, effectively shrinking a vehicle's turning circle to near-pivotal movement.

Pedestrian zones and shared spaces present perhaps the most intriguing challenges for turning radius considerations. As cities increasingly prioritize foot traffic over vehicles, the remaining automotive access points must accommodate delivery trucks and service vehicles without compromising pedestrian safety. This has led to innovative solutions like retractable bollards and dynamic curb systems that adjust based on time of day.

Historical city centers offer living laboratories for studying turning radius adaptations. The winding medieval streets of Rome or Prague demonstrate how centuries-old infrastructure strains under modern vehicular demands. Preservation requirements often prevent significant structural modifications, forcing creative solutions like one-way systems, vehicle size restrictions, and specialized routing for delivery vehicles.

Micro-mobility devices have unexpectedly become part of the turning radius conversation. Electric scooters and compact cargo bikes navigate urban spaces with agility that puts most automobiles to shame. Their presence has prompted some urban planners to reconsider whether traditional turning radius standards remain relevant in increasingly multimodal cities.

The future of urban turning radius design may lie in smart infrastructure. Imagine traffic lights that adjust signal timing based on the turning capabilities of approaching vehicles, or dynamic lane markers that temporarily widen when sensors detect a large truck preparing to turn. Such technologies could help reconcile the competing demands of diverse vehicle types within limited urban spaces.

As autonomous vehicles mature, their turning parameters may redefine urban landscapes. Self-driving cars could theoretically execute precision turns at consistent speeds, potentially allowing for narrower lanes and more efficient intersection designs. However, this potential must be balanced against the need to coexist with human-driven vehicles during the long transition period.

Ultimately, the story of minimum turning radius in urban environments reflects the broader narrative of city life—the constant negotiation between individual needs and collective space, between historical constraints and technological progress. The next time you effortlessly navigate a tight corner or find yourself forced into an awkward three-point turn, remember that you're participating in this ongoing urban dialogue, one rotation of the steering wheel at a time.

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025